Introduction

With the environmental crisis at a critical juncture, today’s mass migration is no longer defined by the historical narratives of nomadic groups and imperial conquests but by the collective hardships of millions internally displaced by an unyielding adversary: climate change. The extraordinary scale of displacement attributable to climate change is illustrated by the relocation of more than 376 million people due to climate-related disasters since the year 2008—an alarming figure equivalent to the total population of Australia applying for asylum each year.

Sample this: In 2022, there were an estimated 36.2 million left stateless from environmental disasters. The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies says projections are that displacements by climate change would double by 2050. India presents both an arena of fragility and a crucible for transformative policy interventions. Here is the microcosm so starkly presented by the Sundarbans delta, straddling the tenuous borderlands of India and Bangladesh: environmental degradation and socio-economic precarity stand as inextricably connected forces. Rising sea levels in the Bay of Bengal-a rise of some 3.2 mm per year, displacing over 70,000 people within the last decade alone.

Shortcomings of COP Initiatives in Addressing Climate-Driven Displacement

The recent Conference of the Parties (COPs) appear to realise the gravity of climate migration, yet repeatedly failed to endorse serious, binding measures that ensure accountability and effective enforcement. This inaction is evident at high-level climate summits, such as the 2021 Glasgow COP26, which set a goal of ensuring global warming of less than 1.5°C without tying participants to any specific targets. CarbonBrief states that they had also failed to equip underprivileged countries with enough capabilities, which would have mitigated or even remediated harmful aspects of climate change. Despite adopting the Glasgow Climate Pact, which urged countries to revisit and strengthen their 2030 emission targets, the summit failed to make any concrete demands. The current NDCs are set to take the world to a 2.5°C warming trajectory, reflecting a significant gap between rhetoric and actionable progress. The failure to attain the $100 billion annual climate finance goal is further complicated by the mobilisation of only $79.6 billion as of 2019. The agreement on “phasing down” rather than “phasing out” coal further diluted its effects, revealing the reluctance of major economies to undertake transformative climate policies. The Refugees for Climate Action network launched at COP29 is a symbolic acknowledgment of the intersection of forced displacement and climate change. While initiatives such as the Loss and Damage Fund, launched at COP27, and refugee-led conservation, like mangrove rehabilitation in Colombia, have enormous grassroots potential, they still lack robust enforcement mechanisms to ensure global accountability.

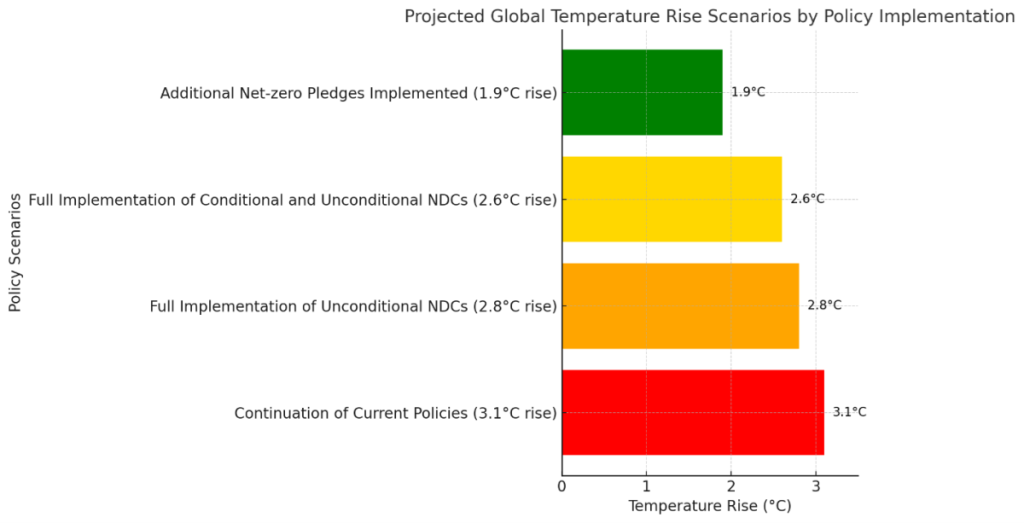

Anticipated climatic extremes across varying levels of global temperature rise

Displacement and Environmental Catastrophes in a Global Context

The increasing frequency and severity of climate-related disasters repeatedly remind us that climate-induced displacement is no longer a distant peril confined to the Global South. From the harrowing destruction wrought by Hurricane Ian in the United States to the record-breaking floods that ravaged Italy’s Emilia-Romagna, climate events now affect communities and infrastructure globally, with developed nations (Global North) becoming progressively susceptible. In 2023, Storm Daniel left Libya in devastating claws, killing over 12,000 people. The first-ever record-breaking temperatures in the Mediterranean were a precursor to a future of relentless climate-driven displacement across whole regions. A landmark study by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center (IDMC) notes that compounded factors make displacement increasingly inevitable: rapid urbanisation, soaring population densities, and climate vulnerability all collide to double the risk of forced migration into the 1970s’ proportions. The fifth and consecutive assessment report by the IPCC in 2019 estimated that sea-level rise (SLR) could submerge between 6,000 and 17,000 km² of coastal land by the century’s end (21000), displacing millions from their homes. Recent initiatives like the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM) on Loss and Damage and the InsuResilience Global Partnership reflect the global character of climate-evicted migrants, but these are not in themselves a tangible action to address international climate migrants. Cities like the Netherlands sit at an existential risk, but large-scale displacement threatens to become a new norm for cities like Mumbai, Shanghai, and Jakarta.

Specifically, Jakarta’s experience accelerated risks because of high subsidence rates that are fueled by excessive groundwater abstraction, exacerbating relative sea-level rise (SLR).The city’s population is projected to reach 30 million by 2030, and the problems Jakarta faces are no different from those in other crowded delta regions, including Kolkata and Dhaka, whose documented subsidence rates of between 6 and 9 mm a year exceed the GMSL. The rates related to sediment loading arising from monsoonal variability are likely to decline with dam schemes that reduce sediment flux by 21%. By 2050, cities such as Bengaluru will provide refuge to nearly 40 million climate-displaced people in South Asia (World Bank,2021), which underlines the urgent need for sustainable resilience strategies in urban planning.

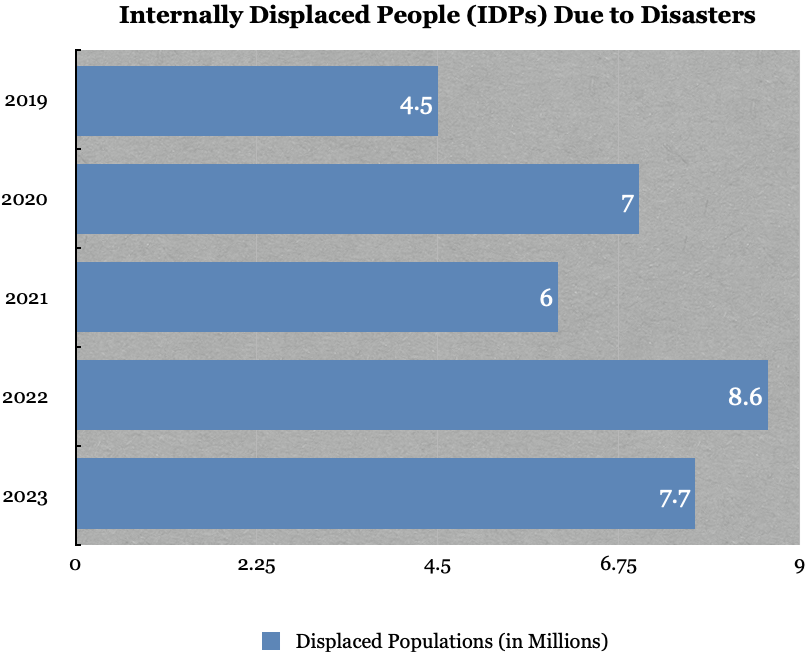

Internal displacements by disasters

The Legal Lacuna: The Status of Climate Refugees and the 1951 Convention’s Deficiencies

Despite increasing visibility, climate refugees inhabit a precarious legal limbo. The 1951 Refugee Convention remains to date the cornerstone of international protection of refugees, but it recognises persons persecuted on grounds of race, religion, nationality, or political opinion alone. Consequently, those displaced by climate change are considered legally invisible, without any rights or privileges attached to being considered a refugee like others. This gap is further intensified by the fact that India remains a non-signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention and therefore does not extend “mandated freedoms of choice” to climate migrants. Such amorphous ‘climate refugee‘ classification under which displaced persons are subjected in host countries, making them open to the possibility of discrimination and exclusion. The ultimate effect is this: policy-making presents a deep hole in this international law-one that COP conferences and allied international bodies must fill lest marginalised populations find themselves languishing in socio-political purgatory.

India’s Climate Migration Crisis: The Silent Exodus and Legislative Void

India stands at the crossroads as an intensifying environmental phenomenon is reshaping its demographic, economic and social landscapes with unprecedented ferocity. Already, an alarming number of people face the threat of displacement, with millions expected to join this climate diaspora over the coming decades. That also explains why in 2020 alone, there were about 14 million Indians who migrated within the country (inter-state migrants) due to weather-related disasters, ranking India third globally in internal displacements, after China and the Philippines. Yet, despite these intimidating realities, the country lacks an organised policy framework to address its climate migrants. Although the 2008 National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) listed measures to fight climate change, it has yet to include particular provisions against displacement. The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), being the primary recipient of complaints, also accepts climate-induced displacement but has no effective financial or legal mechanism to ease the woe of displaced persons.

In a recent legislative effort, the 2022 Climate Migrants (Protection and Rehabilitation) Bill introduced by Pradyut Bordoloi, Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha, seems to be an innovative attempt at codifying protection for those displaced by climate change. By 1985, Assam had lost 7.4% of its land, displacing 5,000 people, especially along the Brahmaputra River. Angered from the story of the inhabitants on the Brahmaputra River – whose livelihoods and dwellings get washed away by the vagaries of every monsoon, the discussion draft also incorporated the concept of a climate migration fund and an outline for ensuring equable treatment and rehabilitation of evacuees. Unfortunately, it did not survive its passage in Parliament, and the subject remains pending for meaningful legislative input at the federal level. In the lack of such a federal apparatus, not only are displaced individuals deprived of the required support, but their responses are also fragmented; lacking coordination between states, they are piecemeal, disjointed, and inefficient force.

The Moral Imperative: Recognising Climate Refugees and Reimagining Global Solidarity

If world leaders cannot overcome their failure to grapple with the climate crisis, humanity will be faced with a double threat: economic destruction and social unrest. The unchecked climate change that would have occurred by 2100 is estimated to impose trillions of dollars of annual economic losses. A 2018 study reveals the staggering cost of adaptation, with relocating communities, construction of seawalls, and rebuilding infrastructure further inland amounting to an almost incomprehensible $14 trillion a year by century’s end—a Sisyphean task against an ever-moving threat. These population relocations also give rise to a new phenomenon known as climate gentrification, in which more affluent households, fleeing from flood-threatened coastal regions, rise to higher-altitude urban areas, inadvertently displacing longstanding residents. Ambition for these stark realities requires not only what can be done but even a more resolute attitude towards transformative policy. Solutions should focus on decreased deforestation and fossil fuel burning, increased investments in renewable energy, and other sound financial instruments like green banks and the Green Climate Fund. But it is precisely this that will not merely be advanced but also legitimised. Any compromises on back-end carbon credits should be ones with high standards, representing reductions in emissions that are real rather than a mirage of “hot air”.

Author’s bio: Hitesh is a student at the Indian Institute of Technology, Patna, with primary interests in applied international development, migration studies, and cultural hermeneutics. He has presented over 10 research papers at prestigious national and international symposia, contributing significantly to critical discourses in these fields. His academic engagements include working as a research intern with the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, and participating in an ANRF-funded project in Kerala.