Introduction

India took a significant legal step to end bonded labour by passing the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act in 1976. This law made bonded labour a punishable offence and formally declared it illegal. However, in reality, bonded labour continues to exist in many parts of the country.

In villages across states like Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Uttar Pradesh, millions of people still suffer in silence. These include men, women, and even children who are caught in a cycle of debt, caste-based discrimination, and extreme poverty. Although they are legally free, they remain trapped in exploitative conditions. Many people work in agriculture, brick kilns, stone quarries, garment factories, bidi-making, and domestic work—often facing abuse, coercion, and the constant pressure of repaying loans they can never escape.

Bonded Labour: A System Disguised by Normalcy

Bonded labour typically begins with a loan taken by a poor family—a few thousand rupees to cover a medical emergency, a wedding, or even just survival. In return, the borrower offers to work for the lender. Over time, this loan balloons due to unfair interest rates, deductions for food or shelter, and manipulation by employers. Entire families become ‘attached’ to the creditor, forced to work indefinitely, sometimes across generations. The modern forms of bonded labour are even harder to detect. Threats, social pressure, and lack of alternatives keep the borrowers trapped. The practice persists as it hides behind other labels— “contract labour,” “advance payment,” or “family tradition.”

Bonded Labour: Statistics

Bonded labour was outlawed in India in 1976 and the government has pledged to identify, release, and rehabilitate approximately 1.84 crore bonded labourers by 2030. According to data presented by the Union government in March 2025, in Lok Sabha, a total of 2,97,038 number of bonded labourers were rehabilitated between 1978 and 2025. Meanwhile, National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data shows that 1,155 cases were registered under the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976, in 2019—96 percent of them involving crimes against SCs and STs.

A Nine-Year-Old’s Death: The Wake-Up Call

In 2024, a tragic case shook Andhra Pradesh—a nine-year-old Dalit boy died after being brutally assaulted while working in conditions similar to bonded labour. He had been working alongside his parents to repay a loan from a local landlord. The news momentarily brought national attention to an issue that largely remains ignored. The structural conditions enabling such exploitation in the form of bonded labour remained unchanged. This incident stresses on the issue of persisting conditions of bonded labour in India. Especially, in a country where the Constitution and the Supreme Court uphold the values of equality, liberty and dignity for all its citizens.

The Triangle Trap: Poverty, Caste, and Weak Enforcement

The persistence of bonded labour is rooted in a vicious combination of poverty, caste discrimination, and institutional indifference.

Poverty: The Economic Noose

Most bonded labourers belong to the poorest and most marginalised sections of society. They do not have land, assets, or savings, which makes them highly vulnerable to any economic crisis.

Caste: The Silent Enforcer

Even after 78 years of Independence, caste continues to have a strong influence on the labour market. According to International Labour Organization (ILO) Report on “Bonded Labour in India: Its Incidence and Pattern” indicates that the incidence of bonded labour remains particularly severe among Dalits and indigenous peoples. The report underscores the deep-rooted caste-based discrimination that continues to perpetuate bonded labour practices. This indicates that Dalits, Adivasis, and backward caste communities are over-represented in bonded labour. Due to social stigma and long-standing discrimination, their problems often go unnoticed and unreported. Many employers, who belong to dominant castes, maintain control over them using threats, intimidation, and sometimes violence.

Enforcement: The Missing Link

Although the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976 criminalises the practice, the enforcement is weak or non-existent. Labour inspectors are under-resourced, and rehabilitative schemes for freed bonded labourers are poorly implemented. When cases are identified, legal processes are slow, and conviction rates are dismal. Victims often lack access to legal aid or the knowledge of their rights. The National Human Rights Commission and NGOs have repeatedly highlighted the gap between legislation and enforcement, but systemic change has been painfully slow. As reported by some of the victims of bonded labour that cases are filed, but follow-up is poor and often forgotten making it a systemic failure. The rehabilitation and prosecution remain significant challenge in eradication of bonded labour.

Government Measures: Well-Meaning but Inadequate

India has introduced several schemes and institutions to combat bonded labour, including:

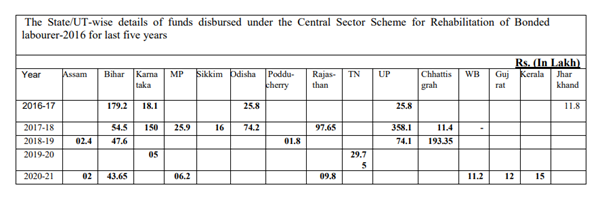

- The Central Sector Scheme for Rehabilitation of Bonded Labourers (2016): This scheme provides financial assistance, vocational training, and support for housing and education to freed bonded labourers, helping them reintegrate into society and break the cycle of exploitation.

- District Vigilance Committees (DVCs): These committees are set up at the district level to monitor, identify, and take action against instances of bonded labour, ensuring enforcement of the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act.

- State-level task forces and awareness programmes: State governments conduct these initiatives to raise awareness about bonded labour laws, educate vulnerable communities about their rights, and coordinate rescue and rehabilitation efforts effectively.

An article from The Wire highlights that rescued bonded workers often face significant delays in receiving full rehabilitation, as the Central Sector Scheme for Rehabilitation of Bonded Labourers only releases payments after the accused are convicted, leaving survivors in limbo even after partial aid. A report from IndiaSpend further notes that delays, unspent funds, and data gaps hinder the effective implementation of rehabilitation schemes. Together, these findings indicate that these programmes are poorly implemented and fail to provide timely support to bonded labourers.

According to the response by the Minister of Labour and Employment in the Rajya Sabha to a question raised by Neeraj Shekhar, only seven states conducted surveys to identify bonded labourers under the Scheme for Rehabilitation of Bonded Labour during the financial years 2017–18 to 2021–22. This limited participation highlights the lack of uniform implementation and weak commitment by many states to actively identify and rehabilitate bonded labourers.

(Source: https://sansad.in/getFile/annex/254/AU1064.pdf?source=pqars)

The data presented in the table highlights a clear lack of proactiveness from many states in accessing funds under the Scheme for Rehabilitation of Bonded Labour. While a few states such as Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Bihar, and Karnataka have received allocations in specific years, several others show negligible or no disbursement at all. This uneven participation indicates not only gaps in the identification of bonded labourers but also inadequate initiative by state governments to fully utilize central support for rehabilitation efforts. Strengthening monitoring mechanisms and ensuring proactive engagement by states is crucial to make the scheme more effective and impactful.

In addition to this, the lack of updated national-level data on bonded labour reflects the apathy of governmental institutions toward this serious issue. Without accurate and current data, the true scale of the problem remains hidden, allowing authorities to overlook it or deny its existence.

What Needs to Change?

To effectively eliminate bonded labour, a comprehensive and coordinated strategy is required:

- Local government officials should have effective systems in place to identify bonded labour. District Vigilance Committees must be made more active, and legal cases against employers should be fast-tracked to ensure accountability.

- Grassroots organisations, trade unions, and legal aid centres should be provided adequate support so that affected workers can seek justice and access rehabilitation programmes. Empowering communities is key to long-term change.

- Policy gap addressing the root cause of people getting trapped into bonded labourer must be mitigated. This includes land reforms, access to fair credit, and expanding rural employment schemes such as MGNREGA in areas most affected by bonded labour practices to reduce economic dependence on exploitative work.

- Bonded labour should not be viewed as a historical issue but as an ongoing human rights abuse. Media, academics, and civil society groups must work together to shift the conversation from sympathy to concrete policy action.

In Conclusion

Ending bonded labour practices requires policy changes, sustained public pressure, better governance, stronger grassroots movements, and ethical business practices. It is also a test of our ability to transform laws into actual-life practices. The death of a child, the silenced voices of millions, and the indifference of systems should compel us to act—not with temporary outrage, but with persistent resolve.

Author’s Bio: Manjiri Dhawade currently serves as a Research Associate at MIT World Peace University, bringing a strong academic foundation with a postgraduate degree in Public Administration. Her expertise and research interest lie in public policy and governance, with a special focus on public service, social welfare, rural development, environment, climate change and sustainability.