As India creates clutter-free streets evicting hawkers, it often ignores the informal economy. Every morning, before Kolkata wakes up, street vendors are already frying ‘telebhaja’, rolling egg rolls, arranging bangles, and selling fresh vegetables. In Kolkata, street vendors are not peripheral; they are social and economic institutions of urban life connecting rural producers directly with urban consumers. For generations, these markets have been the lifeline for sellers and buyers, connecting communities-urban poor, migrant workers, middle class, elite, and thousands more in Kolkata. These vendors, often migrants themselves from rural areas, in the hope of a better life for themselves and their families end up being the flagbearers of micro-entrepreneurship. However, despite playing a critical component in bringing about a positive change, vendors are constantly at risk from eviction, social insecurity, and poor implementation of existing policies to rehabilitate them.

The Role of Street Vendors in Urban Life

Kolkata, hosts an estimated 59,000 street vendors, according to the 2015 survey conducted by Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC) and Town Vending Committee (TVC), although the actual number is calculated to be 2.7-3 lakh. These vendors particularly work in prominent commercial hubs such as New Market, Gariahat, Hatibagan, Burrabazar, B.B.D. Bag and College Street.

At New Market, established in 1874, formal shops offer branded goods, but street vendors clustered right outside have been occupying pavements and roads, leading to serious space issues for pedestrians and vehicles. Garihat, another hotspot for consumers to indulge in saree and jewellery shopping, relishing snacks from street sellers to high-end retailers. The market captures consumers from lower income to middle-class shoppers looking for bargains. Asia’s largest wholesale market, Burrabazar sees daily wage earners, small shop owners and migrant workers sourcing vegetables, spices and kitchenware.

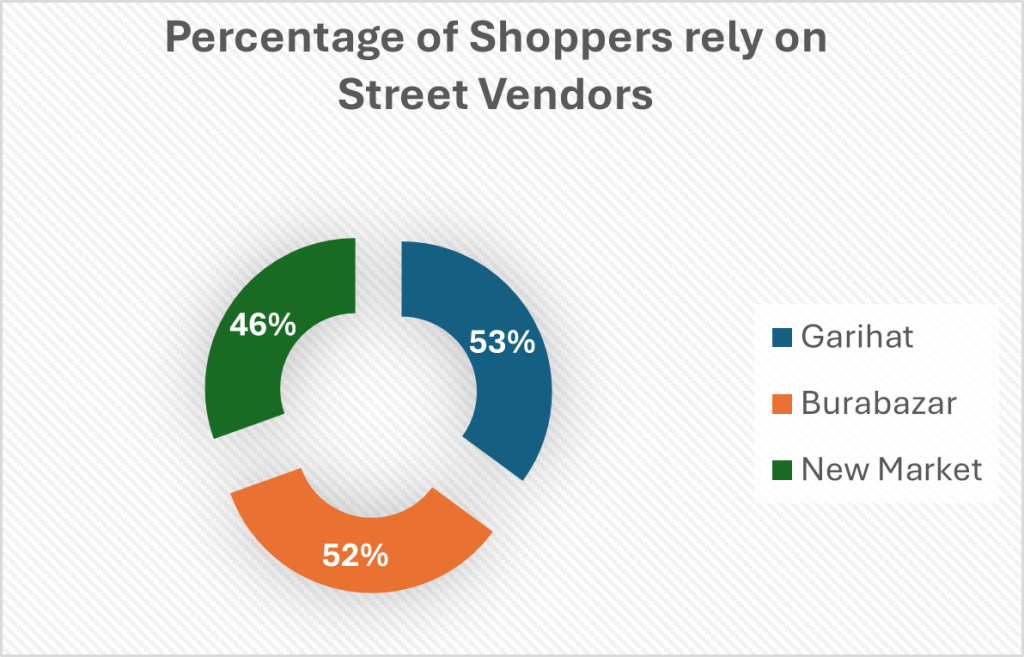

Note: Created by author from the data collected Emergence of Shopping Malls and its Impact on The Hawkers’ Market Economy

According to a survey, 46%, 53% and 52% (fig.1) shoppers at Newmarket, Gariahat and Burrabazar prefer to buy commodities from hawkers for a low price. For many low-income buyers, purchasing small quantities at negotiable prices from vendors is both economical and convenient, especially for Below Poverty Line (BPL) and migrant households managing limited budgets.

Another significant hub is Mullick Ghat, home to Kolkata’s largest flower market, where countless street vendors sell flowers, garlands, and decorative foliage. This colourful market sustains thousands of vendors and workers who contribute to Kolkata’s religious, cultural, and wedding economies. Vendors at Mullick Ghat are integral to preserving traditional livelihoods and cultural expressions in the rapidly urbanising city.

College Street, another place for book hawkers is known as Asia’s largest book market. Alongside branded bookstores selling new releases, numerous street vendors offer both first-hand and second-hand books at significantly lower prices. These vendors also buy used books directly from customers, creating a circular economy that promotes sustainability and reading accessibility for students, working professionals, and low-income residents. This ecosystem allows people with limited means to afford academic and literary resources without relying solely on expensive branded shops.

One of the most vivid examples of street vendors’ necessity is seen at BBD Bag’s Office Para, the hub of Kolkata’s administrative and commercial offices. Here, hundreds of office workers, security guards, delivery boys, and labourers depend on street food stalls selling meals for as little as ₹50.

Livelihoods for Urban Poor: Atmanirbhar Bharat

Street vendors have a great role in contributing to the local economy. It stimulates economic activities by sourcing goods from established businesses and creating backward linkages, increasing competition, generating jobs, and offering low‑price options. It helps the urban poor to sustain their livelihood as they spend a significant amount of their salary on purchasing from street vendors.

Women play a critical role, though often overlooked in this ecosystem. In Gariahat and Burrabazar they sell snacks, flowers, and household items, independently or while assisting family members, earning flexible income that fits around childcare and domestic duties.

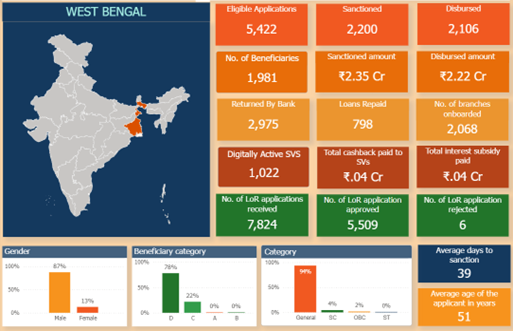

Acknowledging these grassroots contributions, the Government of India introduced the PM SVANidhi (Pradhan Mantri Street Vendor’s AtmaNirbhar Nidhi) Scheme in 2020 to advance the Atmanirbhar Bharat vision of self‑reliance. The programme provides working capital loans of up to ₹10,000, subsidised interest for timely repayment, and incentives for digital payments, while formal registration gives vendors access to wider welfare schemes. In Kolkata only about 5,422 vendors have benefited so far, and many others are excluded owing to documentation hurdles and digital illiteracy. Gender disparity is pronounced, 87% of beneficiaries are men and just 13% women, highlighting barriers such as limited asset ownership, weaker digital access, and restricted mobility for female vendors. To unlock the scheme’s full potential, targeted outreach, simplified paperwork, and digital‑literacy drives especially for women are essential so that street vendors can truly become self‑reliant partners in inclusive urban development.

Policy Gaps and Implementation Failures

Source: Figure adapted from PMSVANidhi Dashboard. Retrieved from https://pmsvanidhi.mohua.gov.in/Home/PMSDashboard

Street vendors undeniably sustain Kolkata’s urban poor by providing affordable goods and creating self‑employment, yet urban development that target “unauthorised” stalls often evict them without offering alternative sites pushing them deeper into poverty. Conversely, enforcement agencies are legally obliged to keep pavements, roadsides, and buffer zones free for pedestrians, traffic and emergency access, and must respond to complaints from residents, traffic departments, and safety authorities. A balanced policy stance must therefore reconcile vendors’ right to livelihood with the city’s duty to maintain orderly, accessible public space through inclusive zoning, substitute markets and participatory regulation.

Recognising this delicate balance and giving importance of the informal sector in the economy, the parliament gave legal rights to these street vendors in 2014, through the Street Vending (Protection and Livelihood) Act, 2014. Despite the government’s approach to provide legal recognition, the failure of proper implementation in Kolkata is causing the street vendor vulnerable. West Bengal notified the West Bengal Urban Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Rules, 2018, under Section 36 of the Act 2014, four years after the central Act was passed, and Section 38 of the Act was passed in 2020, which framed the scheme. KMC constituted the TVCs but the survey and registration of street vendors remain incomplete, limiting the issuance of vending certificates and the creation of official vending zones and resulting in increase of encroachments. The lack of formal recognition remains severe; only about 825 applications registered for licences and among those, 426 received legal licences, limiting others’ access to government schemes. In this absence of licence, most of the vendors are working in an informal environment. These vendors are needed to pay a commission, commonly termed as ‘usuli’, to local enforcement to avoid eviction. This informal rent-seeking not only undermines the Act, but also further marginalises those already struggling for survival.

The Way forward

To transform street vending into a regulated and dignified livelihood option, Indian cities must replace ad‑hoc evictions with structured, rights‑based planning that sees vendors not as encroachers but as vital contributors to urban resilience, employment, and accessibility.

A first step is to rationalise licence caps and upgrade registration systems, for instance, Mumbai, issues only about 15,000 licences for an estimated 2.5 lakh vendors, leaving most unprotected. Licensing needs to become demand responsive, grounded in real time digital surveys, while cities simultaneously expedite the demarcation of vending zones mandated by the Street Vendors Act 2014. Despite Section 38’s provisions, many metros including Kolkata have yet to finish marking “vendor markets” in natural trading hubs; equipping these zones with water, sanitation, and waste disposal services. Physical infrastructure can improve dramatically through public‑private partnerships or Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) funding for modular stalls, shelters, and storage units, while revitalised TVC ensure participatory, real-time governance. Urban design already offers a workable norm, hawkers may occupy up to one‑third of a footpath’s width (as per part 9e) provided the remaining two‑thirds stay clear; consistent ground markings and enforcement of this ratio would safeguard both livelihoods and pedestrian flow.

Financial inclusion programmes such as the PM SVANidhi scheme must be scaled through doorstep KYC, simplified paperwork, and digital‑payment training, especially for women vendors. Crucially, Section 38’s promised welfare benefits provident fund access, education, healthcare remains largely unrealised until vendor identification is complete, rendering the Act’s intent merely symbolic. Full implementation of these measures would protect street vendor livelihoods, enhance urban management, and keep public spaces accessible fulfilling the spirit of the 2014 Act and making Indian cities more equitable, inclusive, and liveable, with vendors recognised as partners rather than obstacles.

Conclusion

Sustaining urban life is an expensive affair. The street vendors provide support for the livelihoods of urban poor, migrants, BPL families and the working middle class by selling affordable goods and two square meals a day. They also create a micro-entrepreneurship eco-system, which makes them the part of Atmanirbhar Bharat. Though Kolkata has made institutional progress under the Act, such as framing rules, forming TVCs, and granting some legal recognition, yet it faces significant enforcement gaps, vendor registration and welfare support. For an inclusive urban development, policymakers and citizens must recognise street vendors as partners. Only then an urban city like Kolkata can grow with the contribution of all sections of society.

Author’s bio: Souparna is a Research Intern at the Bharti Institute of Public Policy, Indian School of Business. He has a Master’s degree in Public Administration and Policy Studies from Central University of Kerala. With a strong background in policy research, he gained first-hand experience working in e-governance at the Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA). He has published several papers and gained exposure at the London School of Economics (LSE) and The World Bank Youth Summit. He has also worked with the New Town Kolkata Development Authority (NKDA), Kerala Institute of Local Administration (KILA), and Young Leader for Active Citizens (YLAC).