Introduction

The conventional approach to development is biased towards parameters assessing and comparing income markers. The Nobel prize-winning economist Amartya Sen, dismisses a simple correlation between national income as Gross National Product (GNP) and people’s living conditions as he highlights the importance of various other variables in a distinction between economic development and economic growth. In this context, it is significant to recognise how good health as a fundamental component of human capital of an individual, society and nation is a factor preceding high income levels and influences well-being. The United Nations (UN) recognises the importance of health for sustainable development as it seeks to promote a people-centred, rights-based, inclusive, and equitable development which enhances well-being.

This blog looks at development holistically through the sustainable development paradigm with a special focus on health. A cross-country analysis of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), GDP per capita and three SDG indicators on health is taken up with a special emphasis on India to understand its status, performance, challenges, and scope vis-à-vis these indicators.

Income: India vis-à-vis Other Countries

A three-decade-long trajectory analysis (1990-2019) of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in current prices (US$ in Billion) based on data from the World Development Indicators of the World Bank Group shows that India was a $320 billion economy in 1990, a year before the liberalisation reforms. In 2005, its economy stood at nearly $820 billion, an approximate 156% rise from 1990; it grew to $2.8 trillion in 2019, increasing 245% from 2005. The percentage change of percentage change between these time periods is 57%. In Bangladesh, the GDP expands from $31 billion in 1990 to $69 billion in 2005, with a 120% rise. Then, with a steep 411% jump, it grows into a $355 billion economy. Here, the percentage change of percentage change is a massive 242.5%. A similar trend of expansion of the economy, albeit lesser, is noticed in Sri Lanka.

In contrast, ‘developed’ countries grew much slower or had declining growth rates in roughly the same period. For instance, the United States (US) grew from a $5.9 trillion economy in 1990 to a $13 trillion economy in 2005 and then climbed to being a $21 trillion economy in 2019 with an increase of 118% and 65%, respectively. The percentage change of percentage change in case of the US is -45%. A similar trend of decline is seen for China and South Korea, attesting to a pattern of faster GDP growth during the initial stages of development and slowing down as national income increases. An analysis of GDP per capita (US$) shows that in 2019, India’s figure was $2050, lower than countries such as Bangladesh ($2122) and Sri Lanka ($4082) and falling way behind countries such as the US, China and South Korea, indicating India’s poor performance in alleviating income inequality.

Health Indicators: India and Other Countries

Health forms a crucial aspect of the agenda for sustainable development and shapes essential capabilities enabling people to contribute to developmental goals. This blog focuses on Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3- ensure healthy lives and well-being at all ages. The target and indicators chosen here are:

Indicator- 3.c.1 Health worker density and distribution

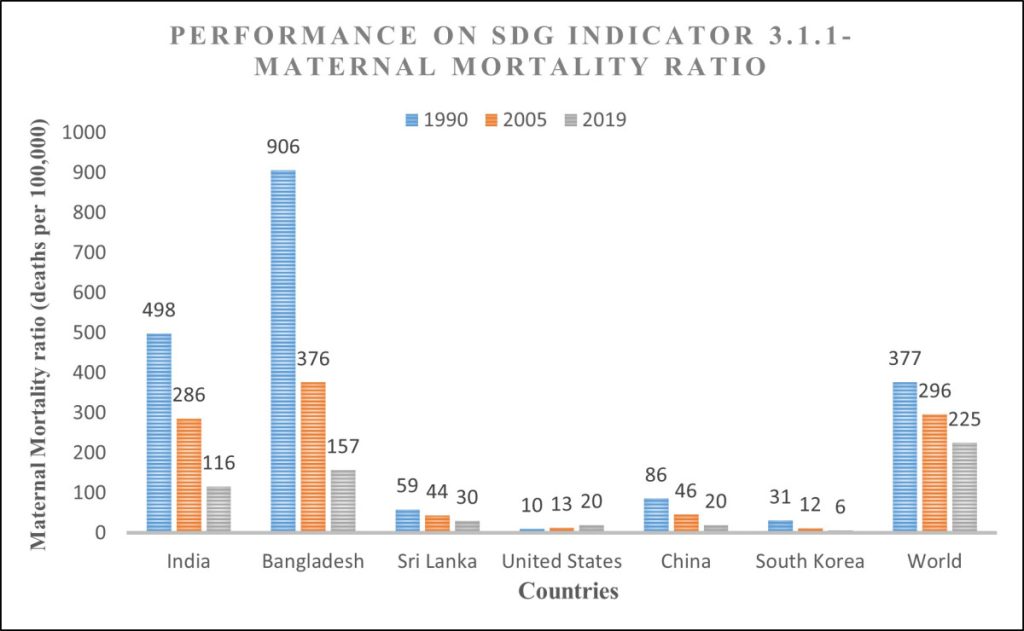

Maternal mortality ratio (MMR) refers to the number of pregnancy-related deaths in 100,000 live births. It’s vital as it informs about the ability of the healthcare system to facilitate safe deliveries and quality of antenatal care and indirectly indicates the status of women and social development in a country. John C. Caldwell identifies factors reducing maternal and child mortality, such as women’s societal status, mother’s education, political determination, and government initiatives in the public health sector. It is also necessary to consider the role of skilled birth attendance while discussing MMR; research demonstrates the negative correlation between MMR and births attended by skilled health staff.

Data Source- Our World in Data, Sustainable Development Goals

Figure: By Author

Data Source- Our World in Data, Sustainable Development Goals

Figure: By Author

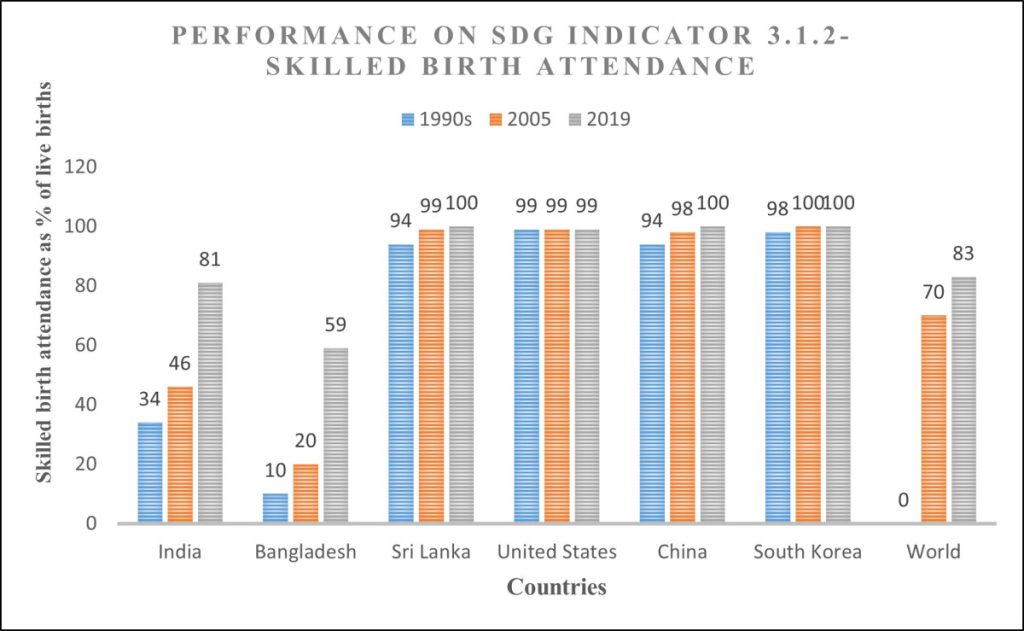

From Figure 1. and Figure 2. (nearest years considered in cases of data non-availability), it can be inferred that MMR reduces with an increase in the coverage of births by skilled health staff (doctors, nurses, and midwives) except for the United States, which S. Dattani points to the change in measurement. The data reveals that among ‘developing’ countries, Bangladesh’s MMR was the highest in 1990, and till 2005, its rate of reduction of MMR was much faster than that of India. With an increase in the coverage of health staff for births after 2005, India witnessed more success in reducing MMR than Bangladesh. The trends in MMR and skilled birth attendance for India communicate that safe and institutional deliveries, antenatal care, healthcare investment and training of good quality medical personnel specialising in obstetrics have become a priority. This enables optimisation of resources such as personnel, beds, and medicines.

Data Source- Our World in Data, Sustainable Development Goals

Figure: By Author

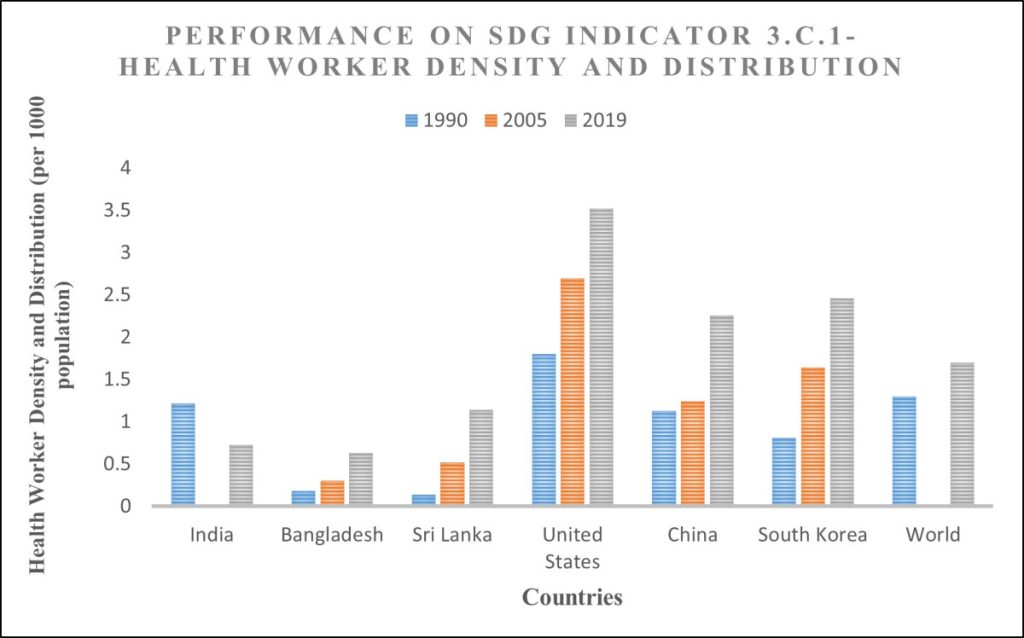

Figure 3. (nearest years considered in cases of data non-availability) shows the health worker density and distribution, defined as the number of medical personnel (surgeons, physicians, nurses, midwives, dentists, pharmaceutical personnel) per 1000 population. This indicator is crucial to understand the status of public health as it tells how well medical practitioners service a population. In 1991, India’s health worker density was 1.22 per 1000 population, and it reduced to 0.73 in 2019. This is dismal considering that China also witnessed a population explosion in the same period but succeeded in increasing its health worker density from 1.13 in 1990 to 2.26 in 2019. India’s performance indicates that population expansion has not seen a commensurate increase in qualified medical personnel, severely impacting timely and reliable healthcare by congesting healthcare delivery, especially for vulnerable sections such as children, women, elderly, etc., who might need periodic medical assistance.

S. Chatterjee reveals that India has demonstrated poor progress in decreasing maternal mortality ratio and increasing health worker density compared to even East Asia and the Pacific (EAP), excluding high-income countries such as China. Another research observes that India’s progress on maternal mortality ratio is lower than the required rate of progress.

Policy Analysis: Findings & Future Directions

The National Health Policy 2017 contains ambitious goals: reducing MMR to 100 by 2020 and meeting health worker density norms by 2020 and 2025 in priority districts. Policy interventions intended to improve MMR and health worker density need to tackle implementation hurdles such as a lack of political will, inadequate financial investment, weak organisational structures, weak stakeholder participation, and weak monitoring systems, in addition to structural challenges faced by the healthcare system such as population expansion, changing disease demography, social inequalities like gender, income, caste, social status and geography, inadequate infrastructure, shortage of trained health workforce, presence of a vast unqualified workforce, shortage of beds, rural-urban divide in healthcare access, private sector bias, international migration of health workers, fragmentation of healthcare delivery and health information systems, high-out-of-pocket expenditure, lack of adequate regulatory oversight and poor law enforcement. Research identifies three types of delays as primary reasons for maternal mortality: in seeking healthcare, in reaching the healthcare facility, and in receiving adequate healthcare; it identifies several challenges in the implementation of maternal healthcare policies, such as income disparities leading to differential regional outcomes, non-operational first referral units (FRUs), high transport costs, poor road infrastructure, inconsistent healthcare provider training which impacts antenatal and intrapartum care, incomplete protocol adoption, and weak feedback loop system.

Several policy-level reforms can help overcome challenges in the healthcare system; regulatory oversight committees must strengthen political accountability, standardise rules and norms across the health sector and improve budgetary allocation mechanisms. Human capital needs to be enhanced through standardised curricula which assess competencies and quality training programmes wherein medical professionals must be mandated to serve in rural areas with adequate incentives, especially specialist training opportunities; telemedicine can also be leveraged to bridge the rural-urban divide. Unrecognised medical practitioners must be brought under the ambit of the state health registry and exposed to licensing programmes. Infrastructural and accessibility issues can be addressed through mobile health units, performance-based first referral units (FRUs), and integrated transport systems. Healthcare delivery can be monitored through digital dashboards, and the promotion of public health insurance schemes can help reduce high out-of-pocket expenditures. Emerging technology such as Artificial Intelligence and machine learning can be leveraged to optimise resource allocation, personalise treatment plans and improve diagnostics. Strategies specifically focussed on reducing MMR can focus upon timely compensation, upgrading training and financial incentives for birth attendants, midwives and community health workers. Their role must be leveraged, especially in providing awareness and equitable access to antenatal and postnatal care in rural and vulnerable areas. Primary health centres must be empowered to facilitate the logistical needs of pregnant women and actively monitor postnatal treatment.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that India’s performance on MMR, skilled birth attendance, and health worker density and distribution continues to remain questionable. Radical policy shifts, a holistic approach to development, and strong implementation mechanisms are required to attain health-related SDGs and provide equitable healthcare by 2030.

Author’s Bio: Ranjit Nath is a postgraduate student of public policy and governance at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Hyderabad. Having worked on an impact assessment project for the Chenchu tribe at Nirmaan and in a multidimensional poverty project with Calcutta Rescue NGO, Ranjit has a strong foundation in qualitative research and complementing it with quantitative insights and policy analysis. His research interest covers areas such as legislative analysis and policy studies.