“…[Y]oung girls enjoyed their early motherhood…[and] revealed that the[ir] favourite part ofbeing a mother was to nurture the child. It [also] gave them happiness” — but at what cost?

The National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-5 (2019-21) factsheet of Meghalaya stated that undernutrition in young girls (aged 15 to 19 years) in rural areas, and among scheduled castes is a common phenomenon. Although the NFHS-5 for Meghalaya represents only 11 districts, collected from 10,148 households: 13,089 of which are women aged 15-49 (including 1,965 women interviewed in PSUs in the state module) and 1,824 men aged 15-54, between 8 July 2019 to 15 November 2019, it is additionally a fact supported by the Social Welfare Department 2021 Meghalaya Case Study.

Physical Complexities and Risks of Teenage Pregnancies

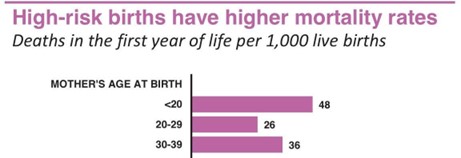

According to the Tanner Stages, the female body reaches puberty and begins development around age 8 and fully develops at the age of 15. However, it is yet another fact that teenage pregnancies are more likely to face physical complications during pregnancy attributing to 17% of maternal deaths, with anaemia being prevalent in 52.5%, and higher frequencies of pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH), pre-eclamptic toxaemia (PET), eclampsia and premature onset of labour (POL). Furthermore, premature birth of babies leads to more complications, such as “higher risks of low birth weight, pre-term birth and severe neonatal condition”.

What is Teenage Pregnancy?

While the female body is considered developed at 15 years of age, this stage is quite a sensitive period of growth, both mentally and emotionally. The frailty of this age is what renders it under the ambit of the definition of a ‘child’, according to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2021 under Section

2(d). As such, any pregnancy between the ages of 13 to 19 years of age is termed as ‘teenage pregnancy’, according to UNICEF. However, since pregnancy is entirely dependent on menarche, which begins between the ages of 10 and 16, this type of pregnancy is also referred to as ‘adolescent pregnancy’ by the WHO; because the term ‘adolescent’ is adjacent to ‘teenager’.

Teenage Pregnancies in Meghalaya

In Meghalaya, the “liberal lifestyle”, noted Dr. Glenn C. Kharkongor, Chancellor of Martin Luther Christian University, Shillong, accounts for teenage pregnancies as “the norm”. But, with increasing awareness and with the implementation of the POCSO Act, it was deemed a problem and there are now consequences to these pregnancies. It is presumed that the rural areas lack awareness and quality education, which grants leeway for rampant teenage pregnancies. Curiously, the urban space, with presumed better access to awareness and quality education notably exhibits higher fertility rates per the NFHS-5 data depicted below.

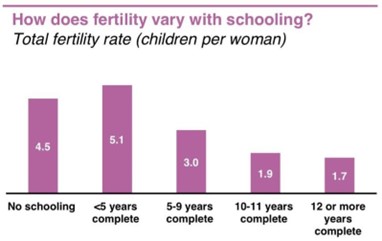

The NFHS-5 denotes 7.2% of all women between the ages of 15-19 years in Meghalaya being pregnant during the survey period of 2019-2020, which accounted for 8.4% of rural area and 3.2% of urban area teenage pregnancies in the State, with the average teenage pregnancy rate in the country standing at 6.8%. Although the percentage is higher in rural areas, the level of education per the graph depicting total fertility rate (children per women) indicate that even education does little to deter teenage pregnancies. With a sample size consisting of 600 male teenagers and 600 female teenagers, the researchers of the 2021 Martin Luthur Christian University (MLCU) study ‘A Report on Teenage Pregnancy with a Special Focus on Familial, Legal and Socio-cultural Context in Meghalaya’ while on the Health and Family Welfare Department Meghalaya podcast, Adolescents Unfiltered, observed that teenagers became sexually active as early as 13 years of age.

As per “Adolescent Girls in the North East: Realising Rights and Navigating Challenges 2019”, girls dropping out of secondary school in the Northeast specifically, Meghalaya is at 20%. When the rest of the country’s dropout rate has reduced significantly, the north-eastern states exhibit an increasing number of girls dropping out of school. In most cases, girls who are pregnant, regardless of their circumstances, get excluded from school.

Fleeting Happiness

Based on the research article “Motherhood Sans Adulthood: Future at Stake”, their sample size of 14 (17 – 26-year-old) females, reveals a positive experience with early motherhood with 14.3% feeling ‘happy/lucky’. The researchers speculate that this ‘happiness’ stems from a “lack of awareness of the consequences”. The 2021 Martin Luthur Christian University (MLCU) study (as referenced in episode 8 of the Adolescents Unfiltered podcast) cites ‘love’ being the leading reason for engaging in sexual intimacy in teenagers below 19 years of age.

While the cause may seem derisory, a deeper delve uncovers the bleakness of broken families devoid of love, ensuing in its pursuance from romantic relationships. The lack in their socio- economic background is yet another driving force for starting families prematurely.

When the euphoria wears off and reality creeps in, a lifetime commitment in the form of an infant deters many young mothers from pursuing their dreams, be it education or career, with

the vicious cycle of poverty disrupting the latter. The article “Unveiling the struggles of Single Mothers in Matrilineal Meghalaya” sheds light on a potential grim future for teenage mothers – barely making ends meet while solely bearing the burden of the entire family, in addition to her newly formed family.

Steps to Abate Teenage Pregnancy

With proper understanding of the gravity of the situation, steps can be taken to mitigate the underlying problem of teenage pregnancies in the State. The Meghalaya Health Policy, 2021 aptly details what changes are necessary to comprehensively address this issue – sincere

endeavour to break social stigmas and taboos related to use of birth control and discussion of teenage pregnancies, respectively, and awareness and capacity building apropos to the phenomenon. The 2021 MLCU study proposes a collaborative effort between parents, society, and educational institutions, tackling the problem from different dimensions.

Author Bio : Liza M. Lamar is a fellow of the Meghalaya Legislative Research Fellowship (MLRF) of the Bharti Institute of Public Policy, Indian School of Business in collaboration with the Meghalaya Institute of Governance (MIG). She has a Master’s in Literary and Cultural Studies, a Bachelor’s in English literature as well as a degree in Law from Khad-ar Daloi Law College, Jowai. Her work experience includes being co-leader of an International Young Adult Network and a digital outreach intern at Advancing North East, an initiative under the Ministry of DoNER and NEC. Her areas of interest are civic management, women’s empowerment, child rights, women’s rights, human rights, LGBTQIA+ rights, disability rights, intellectual property rights and bodily autonomy.

Author Bio : Letitia Iarisa Kharchandy is a fellow of the Meghalaya Legislative Research Fellowship (MLRF) of the Bharti Institute of Public Policy, Indian School of Business in collaboration with the Meghalaya Institute of Governance (MIG). She holds a Master’s degree from Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. She specialises in Equity and Justice for Children and Families. She is passionate about policy advocacy in issues pertaining to human rights violation, combating violence against children and refocusing child rights to education.

DISCLAIMER : The views expressed in this blog/article are author’s personal.