Exploring the labyrinth of identity documentation in India, this blog delves into the complexities and of inconsistencies faced by citizens, while proposing solutions for standardisation and efficiency in the design and management of identity documents.

Introduction

Identity documents are accepted as proof of citizenship and domicile across the world. In India, Aadhaar, a 12-digit randomly generated unique ID backed by biometrics, provides a permanent identification to individuals by the Unique Identification Authority of India. With more than 93.33% live saturation as on 31st December 23, AadhaarSat_Rep_31122023 Aadhaar is one of the “go-to” identity documents…from getting a gas connection, passport, opening bank accounts, buying a mobile connection to accessing government subsidies.

In fact, India has some of the world’s largest social support schemes for its citizens, which means more than half of India’s 1.4 billion population are eligible for the 740 Central sector schemes (CS while 65 (+/-7) “Centrally sponsored schemes” (CSS), funded by the centre and implemented by 28 states across the country.

To ensure these are delivered efficiently and effectively, every ministry delivering the schemes uses a “Know your customer – KYC identity document that provides a “Proof of citizenship and/or Proof of residence” that eligible beneficiaries submit for verification and approval before enrolment into the schemes.

Despite Aadhaar becoming the primary “go-to” identity document in the country, beneficiaries have to use multiple other identity documents for a specific service, such as ABHA card – a 14-digit number to uniquely identify an individual in India’s digital healthcare ecosystem, ration card for food subsidies, pensioner’s card for pension’s, Voter ID card for casting vote, PAN card for tax identity among others.

How many Identity documents do citizens in India have access to?

As per information available, Indian citizens can have between 22 and 32 identity documents issued by some of the 58 central government ministries and 28 state governments, apart from eight union territories and their respective government departments.

For instance, the Department of India Post, Govt of India which besides delivering mail, accepts deposits under Small Savings Schemes, provides life insurance cover, also helps with the wage disbursement for the Government of India under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) and old age pension payments; provides a “List of 22 acceptable documents as Proof of Identity with all requiring photographs; and 25 Proof of Address documents with variations in J&K, North East and Assam Service Areas identity and address proof .”

A dipstick study showed that an Indian citizen owns/uses between three to eight “proof of identity/address” documents, with the most common being Aadhaar, PAN, passport, voter ID, and driving license in the urban areas, while semi-urban and rural areas own and use Aadhaar, Ration card, voter ID, bank passbook, Kisan Passbook, Land ownership documents among others.

This multiplicity of identity documents, though designed to help the citizens, actually hamper many, as the documents are replete with “data inconsistency” that affects them on a daily basis across the country.

Essentials of “Data Consistency”

For this to be ensured, the primary factor is “data consistency”, considered one of the most important elements of data quality, comprising uniformity, accuracy, and coherence across the board. So how does the lack of “data consistency” affect Indians? If one were to go by the correct and consistent spelling of a name as an example of data consistency, many citizens in India are victims of inconsistency and discrepancies in their names, addresses, etc. Evidence of this opaque yet critical issue shows up across the country every day as citizens line up at government services facilitation centres for resolution. For instance, retirees are unable to access their Provident Fund accounts till all the documents are in sync, property documents cannot be registered with such discrepancies, one cannot access government subsidies like PDS, gas connections, etc., banks do not settle accounts of demised due to incorrect name of account holders or nominees among others.

Estimated Prevalence of Data Inconsistency and Some Reasons?

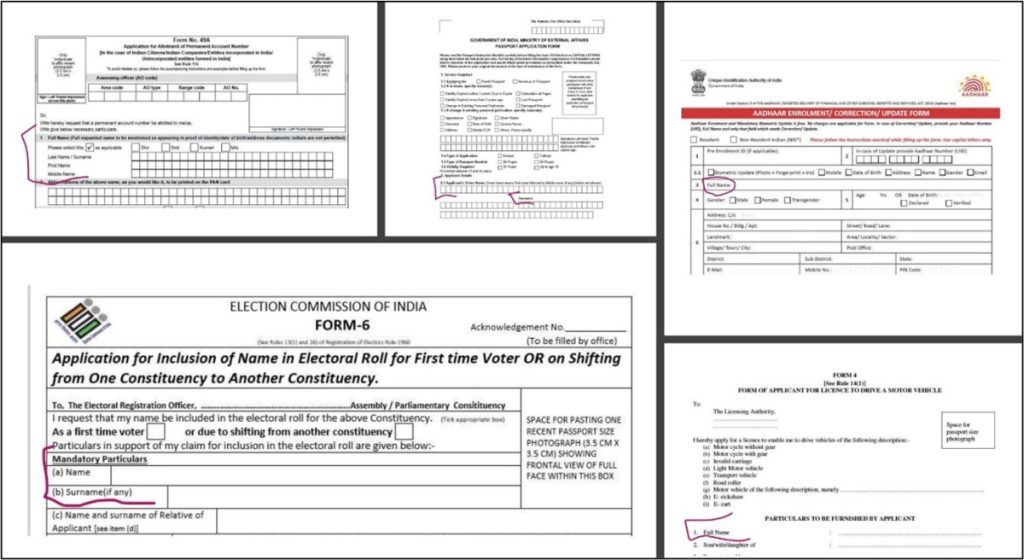

A topline analysis of the five most used ID document application forms shows that data inconsistency pertaining to names starts at the application stage, as no two agencies seek the name to be filled in the same order, nor do the nomenclature match with the other one. Besides variations in name fields and nomenclatures, the list of acceptable (Proof of Identity – PoI) documents too varies with different agencies. Interestingly, acceptable documents differ from other states, such as J&K, Northeast, and Assam Service Area. No two forms of this wide-ranging list of documents are standardised or have a universally acceptable format, which perhaps results in an extremely high rate of data inconsistency. Even the most commonly used documents among urban citizens, such as Voter ID, passport, Aadhaar, PAN and Driving Licence, suffer from data inconsistency.

Source:* Aadhaar enrolment form uidai.gov.in Passport application form Indian passport PAN application form Income Tax Department form-6-application-form-for-new-voters Election Commission of India Driving License – Telangana Telangana, State of India

With India’s naming conventions being as divergent as its geography, differing from one region to the other, community and family, the “Full Name” as asked in the Aadhaar application leads to further unintended issues as India, with its cultural diversity, has different ways of using a “Full Name.” These inconsistencies cause a lot of inconvenience to citizens, with the most frequent pain points while undertaking corrections being – multiple visits to service centres, paperwork containing copies of other documents, which could include notarised documents and time for corrections taking between a week to 30 days, and the inability to access services till resolution.

High Rate of Inaccuracies and Data Entry Errors

The other reason for the data inconsistency is the inaccuracies and data entry errors that creep in during the manual process of data/information transfer from offline/printed to soft/electronic forms that eventually get passed on to the citizen. Mostly, data collection and entry into government databases is outsourced to external agencies. Hence, the governments feel no responsibility for its accuracy, as per internet-governance “Accountability for accuracy of data – Frequently data that is collected and entered into government databases is not accurate, because the departments are not collecting the data themselves. Thus, they feel no responsibility for its accuracy. If a mechanism is built into each database for identification of each data source this brings accountability for data accuracy.”

Cost of Rectification

The economic costs, impact, and loss of productivity due to this issue to both government and citizens are quite humungous. According to a rough estimate, it takes a citizen in a metro area a minimum average of Rs.1000+ to get the documents rectified. Extrapolated countrywide, the implications are quite substantial.

The Way Forward

Among others, two rather simple solutions can drastically improve data consistency, with the first being standardisation or adoption of common minimum standards across central/state governments/inter agencies in how critical information is sought. The second solution is maximising error-free data transfer from paper when done manually by service providers, data cleaning with random quality checks of outputs and passing the burden of accuracy to the service provider rather than to the citizens. However, the standardisation or ensuring common minimum standards nationally will firstly need acknowledgement of the issue and the coming together of central and state governments and multiple departments to agree on and adopt common minimum standards which can be a tough call.

Author’s Bio: Kalyani Prasad is a Strategic Marketing, Behaviour Change, and T4D specialist and consults for the Global Health and Development sector in LMIC’s. With 20+ years’ experience across 10 countries in growing markets for products, services and enabling long term behaviour adoption, she has led large-scale, strategically important projects for UN, non-profits, and the private sector. A Sociology Masters from Annamalai with training in IMC-COMBI at Steinhardt-NYU, she formerly worked for Saatchi & Saatchi, PATH, UNICEF, Malaria Consortium among others. Her background also includes Journalism, Advertising and Operations.

DISCLAIMER : The views expressed in this blog/article are author’s personal.