Introduction

Substance abuse is a persistent challenge impacting not only public health, law, and enforcement but also social stability, economic productivity, and institutional capacity. From alcohol to opioids and synthetic drugs, India, like many other countries has been battling addiction for decades now. But, in past few years, the magnitude and scale of the problem especially among youth and marginalised communities, has led to bigger issues. What was once viewed primarily as a health issue has now escalated into a multidimensional crisis that strains law enforcement, exposes policy gaps, and demands a coordinated, long-term response.The 2019 report by AIIMS on the magnitude of substance use in India revealed that over 5.7 crore Indians were affected by substance use disorders, with more than 2.6 crore using opioids and around 16 crore consuming alcohol, often in harmful or dependent patterns.

At the global level, the UNODC World Drug Report 2024 highlights a 20% increase in drug use over the past decade, with 29.2 crore people using drugs in 2022. Despite 6.4 crore people globally suffering from drug use disorders, only 1 in 11 receive treatment implying a lack of access to treatment.

A Growing Divide: Drug Arrests and Treatment Access in India

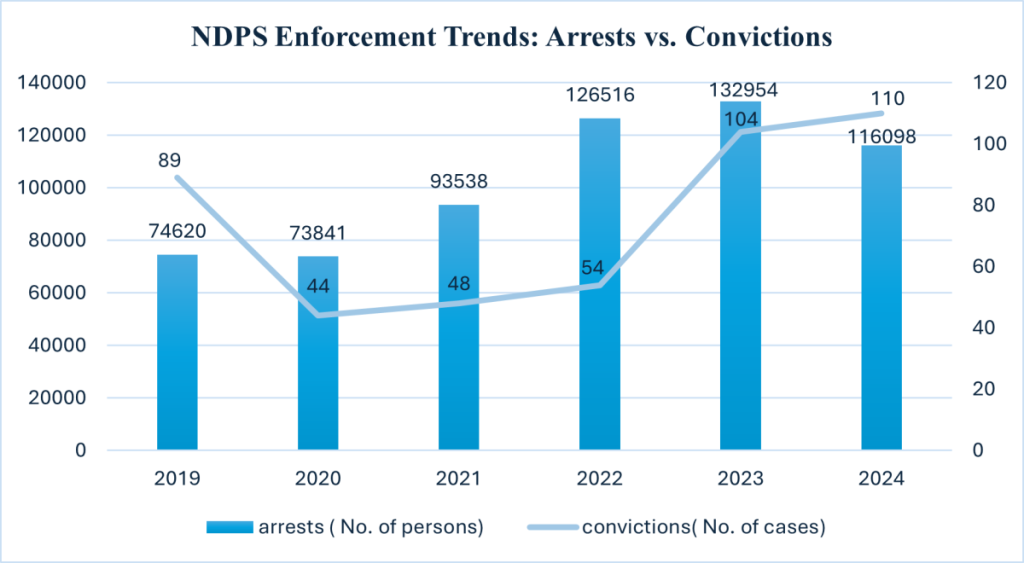

Despite the alarming figures, India’s policy response remains heavily skewed towards law enforcement over rehabilitation. Arrests under the NDPS Act rose from 73,841 in 2020 to 1,16,098 in 2024, while access to treatment services remains limited and uneven. The situation is particularly acute in Punjab with 66 lakh drug users, and Kerala has witnessed a dramatic surge in synthetic drug use, especially MDMA, resulting in a 330% rise in registered drug cases between 2021 and 2024. Combined with persistent social stigma, these conditions continue to discourage individuals from seeking help, reinforcing cycles of addiction and marginalisation.

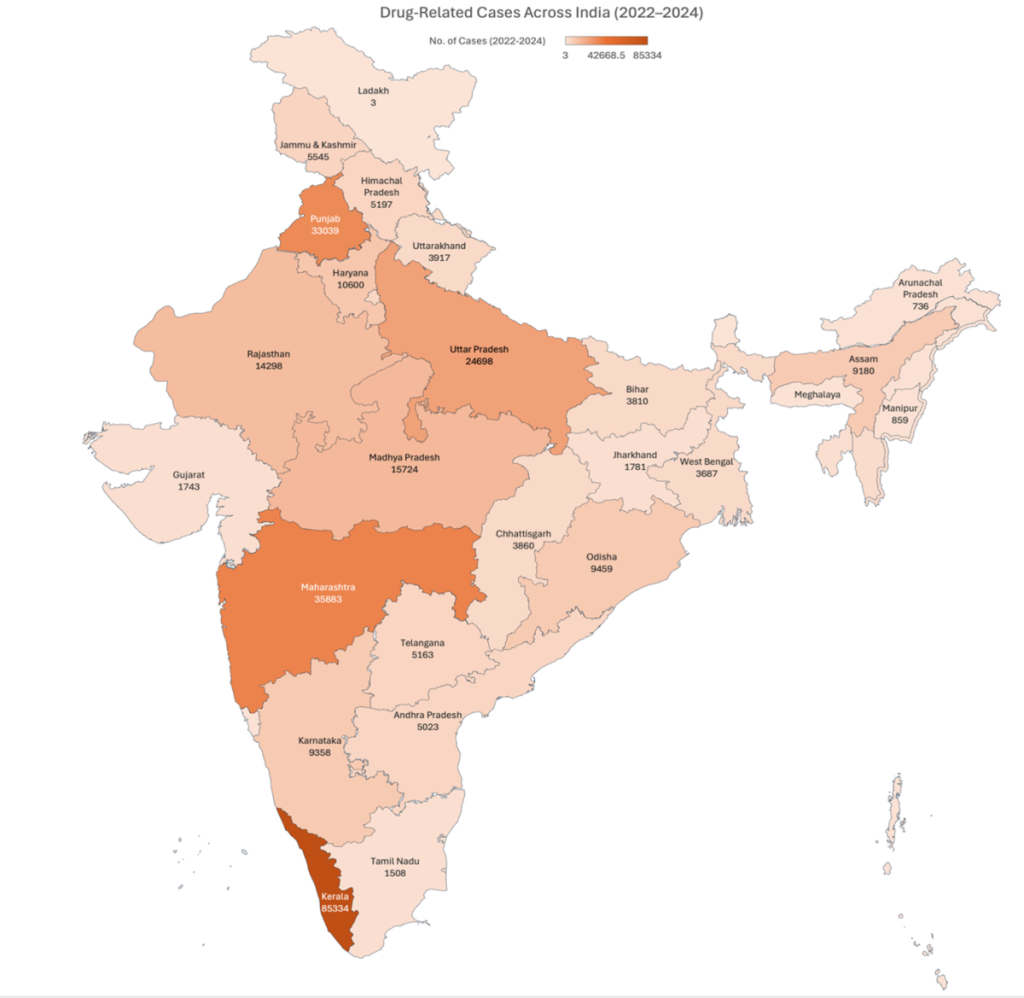

The heat map below visualises the total number of drug-related cases reported across Indian states over the past three years. States like Punjab, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, and Kerala stand out with consistently high case volumes. While this reflects enforcement activity, it also signals deeper patterns of substance use prevalence and trafficking intensity in these regions.

Retrieved from https://sansad.in/getFile/annex/267/AU1508_qqxsW2.pdf?source=pqars

India’s Policy Approach

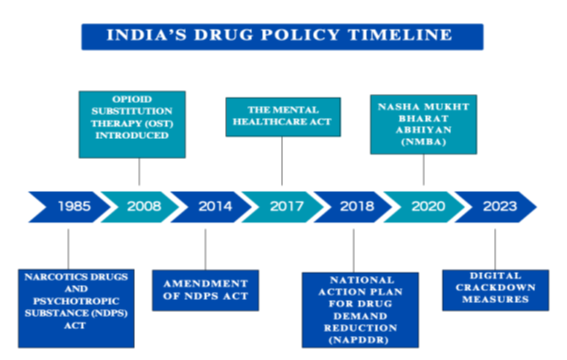

India’s backbone response to substance abuse is primarily supported by the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act, 1985 which criminalises the production, possession, sale, purchase, and consumption of drugs. Although it includes provisions for rehabilitation, in practice, users are often treated as offenders rather than patients.

Recognising the gap, the government introduced the National Action Plan for Drug Demand Reduction (NAPDDR) in 2018 to shift its focus on prevention, awareness, and rehabilitation. Under this, the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment (MoSJE) and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare have supported the creation of rehabilitation centres and Opioid Substitution Therapy (OST) programmes.

One of the government’s flagship initiatives, Nasha Mukht Bharat Abhiyan (NMBA) operates across all state districts via 10,000 volunteers, reaching over 14.79 crore people, including youth and women. 350 Integrated Rehabilitation Centres for Addicts (IRCAs) that provide reintegration, counselling, and detox were opened in 2022. To support at-risk children, drop-in and peer-led centres offer safe spaces for assessment and referral.

To expand institutional care, the government has also strengthened medical infrastructure for addiction treatment. Addiction Treatment Facilities (ATFs) and District De-addiction Centres (DDACs) now offer structured, multi-disciplinary treatment. Awareness is supported through Navchetna school modules and a toll-free helpline (14446) for parents, teachers, and students.

In FY 2024–25, the MoSJE allocated ₹333 crore to NAPDDR, up from ₹260 crore the previous year, signalling increased policy focus. However, despite record drug seizures worth ₹16,914 crore in 2024, many programmes still suffer from limited reach, fragmented implementation, and underfunding, particularly in rural and underserved regions.

Widening Policy Gaps

Rising Arrests, Low Convictions: Despite stringent policies adopted by the government, drug-related crimes and consumption continue to increase. According to the Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB), India recorded 1,16,098 arrests under the NDPS Act in 2023. However, conviction figures remain disproportionately low, with only 110 convictions reported in same year, especially for high-level traffickers. Corruption within enforcement agencies remains a critical challenge. Drug syndicates have reportedly known to bribe police officers, customs staff, and field agents to leak raid information or facilitate trafficking routes. In 2024, two Chennai police officers and an NCB official were arrested for allegedly tipping off traffickers about impending raids. Similarly, in 2023, the CBI initiated an inquiry against former NCB Zonal Director Sameer Wankhede for allegedly seeking a ₹25 crore bribe in connection with a high-profile drug case.

Retrieved from https://sansad.in/getFile/loksabhaquestions/annex/184/AU223_Gq8wnM.pdf?source=pqals

Inaccessible and Underfunded Rehabilitation: Rehabilitation centres remain underfunded and often inaccessible to most users with a lack of trained medical staff and insufficient beds, especially for rural and underserved urban areas. Social stigma further discourages people from seeking help and accepting the problem. In Ludhiana, Punjab, one of the worst-affected districts, the only government-run de-addiction centre saw patient numbers rise from 80 in 2021 to 196 in 2024, yet lacks a full-time psychiatrist and adequate staff. Many families with no affordable public inpatient options rely on private centres charging ₹30,000–₹80,000 per month. Nationally, the 2022 AIIMS-NIMHANS found that only 1 in 10 people with substance use disorders receive treatment, reflecting a deep mismatch between need and care availability.

Youth Exploitation: Drug peddlers exploit vulnerable youth in urban slums, initiating them into both substance abuse and crime. A 2023 cross-sectional study in Delhi found that 49% of street children aged 7–18 had used substances in the past year, with peer influence acting as a key driver. Similar results are seen in the states of Punjab, Haryana and all over India. These figures point to a systemic failure of not just of law enforcement, but of education and community support.

The result is a system that penalises rather than rehabilitates, missing the opportunity to treat substance abuse as a public health issue.

Best Practices: Home and Beyond

At the state level, promising trends are starting to appear in India. A community-based approach to addiction treatment has been adopted in Sikkim. As part of Tamil Nadu’s ‘Drug-Free Tamil Nadu’ initiative, Anti-Drug Clubs were established in government schools, organizing activities such as sports events and martial arts workshops to engage students and promote drug de-addiction through positive outlets. Kerala launched the Student Police Cadet (SPC) Project, which combined awareness-raising, athletics, and discipline in an after-school format. These programmes show that decentralised, community-led interventions can complement and support stringent policies.

Several countries offer models worth emulating. Portugal’s 2001 decriminalisation policy, which focused on treatment over incarceration, led to a 75% drop in drug-related deaths and crime by 2022. Another example is Iceland, which decreased teen drug usage from 42% in 1998 to 5% in 2016 by combining rigorous advertising bans, controlled alcohol availability, and after-school sports and art programmes.

Policy Recommendations

In its fight against rampant drug abuse, the government of India needs to shift the focus of policy from criminalisation to care by adopting the following:

Reforming NDPS Act: By learning from the Portugal model, adopt mandatory rehabilitation for first-time offenders, which will provide medical and psychological support and treat addiction as a health issue rather than a criminal offence.

Strengthen Youth Engagement & Education: India can learn from Iceland-inspired after-school programmes and adopt initiatives which combine sports, arts, counselling, and mentorship to reduce idle time and peer pressure among at-risk youth. Awareness tools such as street plays, peer mentoring, and community campaigns should be scaled up in slum areas and schools. Implement stricter control of advertising restrictions around schools and limit access to tobacco and alcohol to minimise youth exposure.

Support School Dropouts through Skill Development: Connect school dropouts with skill development programmes through mobile learning hubs and community education centres in risk-prone areas. Pilot Dropout Recovery Circles based in Iceland, matches young persons with mentors, imparting vocational skills and guidance in preventing them from getting into addiction cycle.

Revamp Rehabilitation Centres: Scale up government rehab centres with qualified staff and affordable access in underserved areas. Mandate annual surveys and public audits to ensure accountability, improve infrastructure, and monitor service quality, with options for follow-up care, job training, and social reintegration.

Conclusion In India, substance abuse is not just a legal but also a social, psychological and developmental challenge. While enforcement is crucial, the government must make more efforts to focus on rehabilitation, prevention, and reintegration. India can evolve a more holistic and comprehensive policy that views addiction as a health issue by taking inspiration from international models and scaling up effective local projects. To move towards a drug-free and resilient India by 2047, a combination of rehabilitation, technology-driven enforcement, youth involvement, and economic reintegration would be essential.

Author’s Bio: Aashima Chitkara is pursuing Master’s in Economics at Ashoka University, with a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (Honours) from Panjab University. She is currently interning at the Bharti Institute of Public Policy as Research Intern. She previously interned at NITI Tantra, wherein she worked on policy briefs, addressing key social issues and policy gaps. Her academic and professional interests lie in macroeconomics, international trade, public policy, and evidence-based research.