Among the many forms of gender inequality—unequal pay to underrepresentation in political arenas, perhaps the most severe and neglected is the unequal food system, where women disproportionately suffer from food insecurity. Hunger isn’t a new problem, and neither are its root causes. What’s new today is that we’re facing many crises at once – climate change, conflicts, economic troubles, the impact of the pandemic, and the Russia-Ukraine war, all making hunger worse. These factors have worsened social and economic inequalities and have slowed or even reversed progress done so far in reducing hunger across many countries. Of the 343 million people who are extremely hungry worldwide, nearly 60% are women and girls. Around 126 million more women than men are unsure of their next food source or if they will have one.

Achieving zero hunger is a fundamental objective of the Sustainable Development Goals. It focuses on removing hunger, ensuring food security, improving nutrition, and advancing sustainable agriculture. This blog prompts important considerations about the benefits and opportunities associated with these objectives and if these are equitably available to everyone.

Introduction

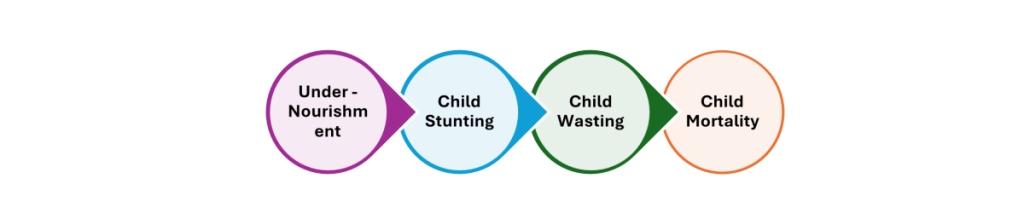

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is a tool used to determine and track hunger in different countries. It helps understand how serious hunger and undernutrition are around the world. GHI scores are based on the values of four component indicators:

Undernourishment is defined as the proportion of the population with insufficient caloric intake. Child Stunting reflects the percentage of children under five who display low height for their age, a clear indicator of chronic undernutrition. Child wasting is the measure of children under five with low weight for their height, highlighting acute undernutrition. Finally, child mortality encompasses the share of children who do not survive past their fifth birthday, primarily because of the lethal combination of inadequate nutrition and poor health conditions.

Women are life-bearers and the cornerstone of a healthy and productive society. As women and children are typically at a higher risk of food insecurity and hunger, they are more likely to develop deficiencies caused by undernourishment. Turning the lens to India, where gender inequalities are deeply ingrained, its GHI score highlights that economic advancement alone cannot eradicate hunger. A more comprehensive approach is necessary to address the fundamental causes of malnutrition.

Malnutrition Among Women in India: A Persistent Challenge

Despite progress in women’s rights, within many homes, women still face deep-seated inequality when it comes to food distribution. This leads to higher rates of malnutrition and anaemia in women, perpetuating a generational cycle of poor health.

Over one billion girls and women around the world face undernutrition, lack essential vitamins and minerals, and suffer from anaemia. India has a severe hunger level, with a score of 27.3 on the 2024 Global Hunger Index. With 13.7% of its population undernourished, India ranks 105th out of 127 countries in the Global Hunger Index.

Figure Source: Global Hunger Index

Women comprise 48.4% (2023) of the population and are the most vulnerable to food insecurity. The disproportionate nutrition to women and their bad health bears generational consequences. It is a proven fact that an undernourished mother bears and gives birth to an undernourished baby and is vulnerable to all kinds of health issues. Maternal undernutrition is estimated to account for 20% of childhood stunting. The NFHS-5 (2019-20) Report highlights concerns about women’s and children’s nutritional levels and anaemia. The percentage of stunted (35%), wasted (7.7%), and underweight (32.1%) children has increased substantially. According to the report, only 11% of breastfed children have an adequate diet, with 35.2% of them falling under infant mortality.

Around 57% of women (aged 15-49 years) are anaemic, with 52.2% of pregnant women (aged 15-49 years) suffering from anaemia in 2019-20, and 18.7% are underweight.

Figure: Provided by author

Poor nutrition in girls and women can weaken their immunity, affect brain development, and increase risks during pregnancy and childbirth. This also harms their children’s chances of staying healthy, growing well, learning properly, and earning in the future.

Figure: Provided by author

While schemes like Poshan Abhiyan, launched in 2018, focusing on the nutrition level and status of adolescent girls, pregnant women, lactating mothers, and children from the age of 0-6 years, have shown slow progress. The programme, with technology convergence and community involvement with a targeted approach, seeks to reduce hunger, under-nutrition, anaemia, and low birth weight in children and focuses on mothers, thus holistically addressing malnutrition. The stunting of children is still high as compared to other countries, stating that the change is slow and uneven, particularly in rural areas where traditional gender norms further limit women’s access to resources.

Also, schemes like the public distribution system and mid-day meal, which focus on improving food security, need a revamp to target the most under-fed population with a focus on expanding the food basket. UNICEF’s nutrition programme in India focuses on improving pregnant women’s nutritional outcomes, however, their success rate is low.

Several variables and factors affect a woman’s and children’s well-being. Less participation in the workforce, climate effects, economic crisis, lack of education access, and many more add to the problem. Less decision-making power in family issues or owning property adds up to women’s suffering. 56% of women don’t own property, and 22% lack bank accounts that they use by themselves.

Uplifting Measures

While the situation remains dire, several key measures can uplift women and communities. Addressing hunger in a gender-sensitive way is paramount. Programmes that specifically target women’s nutritional needs and empower them economically can play a crucial role in reducing food insecurity-

Community Nutrition Hubs: Women-led community kitchens are vital in providing affordable, nutritious meals, promoting healthy eating habits, enhancing economic empowerment, and improving food security and community well-being.

Direct Benefits for Women: Implementing cash transfers and food subsidies specifically for women helps address gender disparities in food access and enhances equity.

Empowering Women Farmers: Access to credit, land ownership, and tailored training for women farmers boost sustainable agriculture, increasing their contribution to food production and agricultural growth.

Strengthening Maternal and Child Health: Expanding maternal health programmes, including free nutritional supplements during the first 1,000 days of a child’s birth, is important for preventing malnutrition and promoting healthier generations.

Adopting Gender-Sensitive Food Security: Food security initiatives must prioritise women’s nutritional and economic needs, ensuring inclusivity and addressing unique challenges faced by women in agriculture.

Women’s Education and Skill Development: Encouraging girls’ education and providing vocational training for women is essential for improving economic resilience and combating root causes of food insecurity.

Facilitating Women’s Workforce Participation: Overcoming barriers such as insufficient childcare and unsafe working conditions is vital for enhancing women’s participation in the labour market and advancing economic equality and empowerment.

Conclusion

Inequalities against women are not just a women’s issue but a societal issue. Women’s empowerment does not guarantee success. Ensuring food security for the nation alone is not adequate to ensure food security for women. Breaking the cycle of gendered hunger and health inequalities requires sustained and targeted policies that prioritise women’s health and empowerment not just at the community or national levels but at the household level too. This is the only way to ensure that food security benefits reach the most vulnerable and provide future generations with a brighter, healthier future.

Author’s Bio: Aastha Kaura works as Research Assistant at the Bharti Institute of Public Policy (BIPP), Indian School of Business (ISB). With a background in Computer Applications, she is passionate about using technology to drive meaningful policy research. She was a part of the Tech Policy boot camp held by BIPP and contributed to evaluating government services in Himachal Pradesh under the NeSDA framework. Her research interests lie at the intersection of gender studies, climate change, crime studies, and evidence-based public policy.